Nvidia’s growth has been meteoric — can anything get in its way?

Eric Schmidt, Google’s former chief executive, appeared to have an investment tip for Stanford University students during a seminar last week.

The billionaire angel investor told students in a recorded discussion that the “amount of money being thrown around” in artificial intelligence is “mind-boggling”. “I’m talking to the big companies, and the big companies are telling me that they need $10 billion, $20 billion, $50 billion, $100 billion.”

He said: “If $300 billion is all going to Nvidia, you know what to do in the stock market,” before quickly adding: “That’s not a stock recommendation, I’m not licensed.”

Nvidia’s growth keeps coming. Later this month, analysts expect the company to announce 112 per cent year-on-year sales growth to $28.6 billion for the second quarter, with operating income up 142 per cent to $18.8 billion, according to FactSet data.

The semiconductor specialist, which was briefly the world’s most valuable public company in June with a valuation of $3.35 trillion, has been the undisputed leader in the race to produce chips that power AI growth.

However, stoic holders of its stock have suffered multiple cases of whiplash this month as some investors took profits amid concerns about the risk of an “AI bubble”, fuelled by reports of delays to the release of Nvidia’s new Blackwell chip.

Other investors, who are more bullish about the prospect of an AI revolution, have seen the dips as a buying opportunity. After a sharp fall in shares, Nvidia’s valuation has since recovered to $3.06 trillion, trailing Microsoft’s $3.11 trillion and Apple’s $3.44 trillion.

Wall Street analysts say they are forever fielding questions about Nvidia. So how secure is its market dominance?

Founded in 1993 and based in Santa Clara, California, the company claims to have invented the graphics processing unit (GPU) in 1999. The hardware features electronic circuits that can perform mathematical calculations on large datasets in parallel and at high speed.

In 2006, Nvidia launched its own programming language for GPUs, called Cuda, which is taught to budding software engineers in universities and can only be used on its chips.

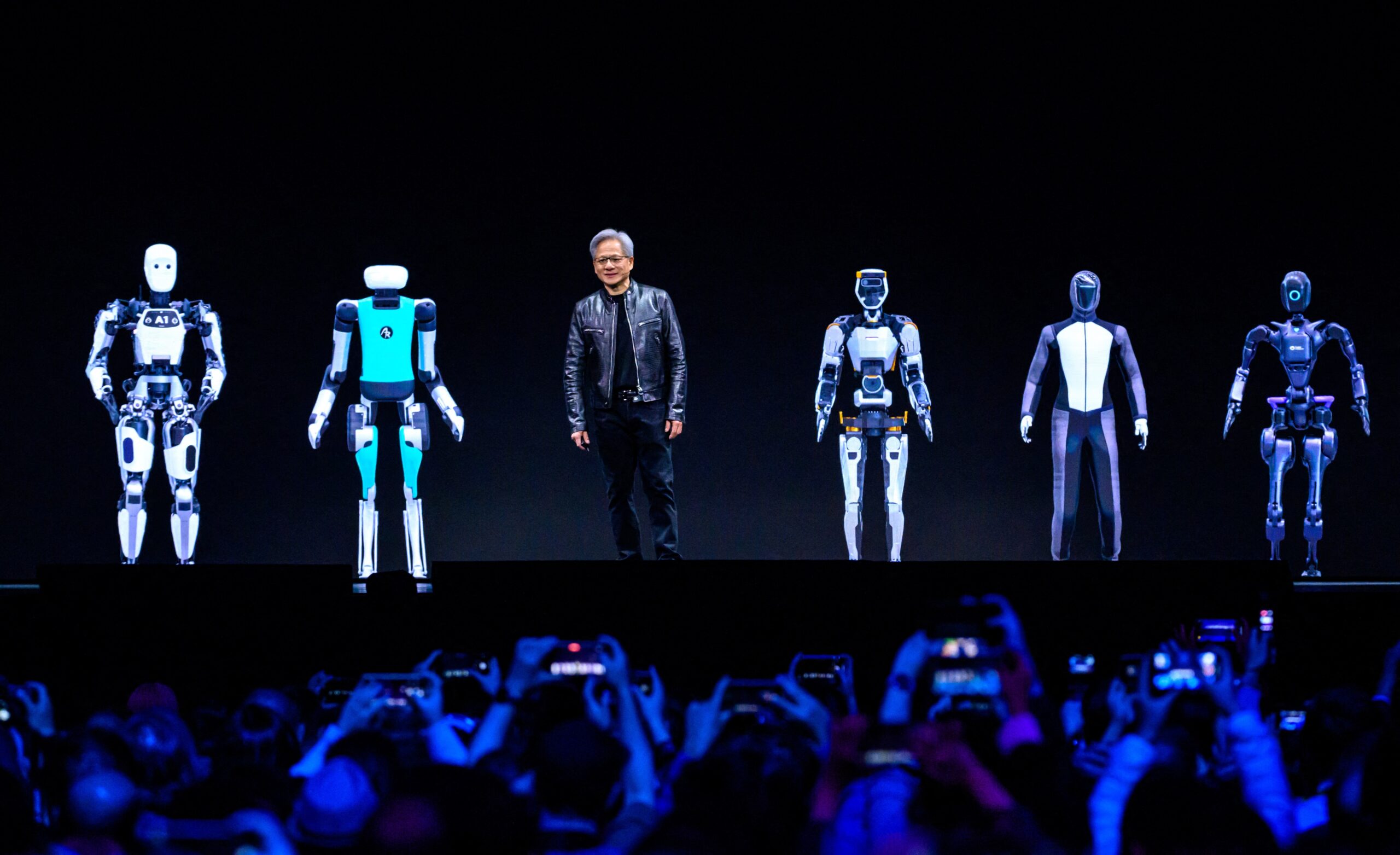

For decades, Nvidia’s GPUs were used to power the creation of high-resolution images used in video games. However, they are now used by more than 40,000 companies, from carmakers and drug discovery businesses to weather forecasters and social media giants chasing superfast computing speeds to make the most of software developments such as generative AI.

In the first quarter of the year, Nvidia won 88 per cent of the GPU market, up from 84 per cent a year ago, according to Jon Peddie Research.

Advanced Micro Devices, its biggest rival, which offers cheaper GPUs, controlled 12 per cent in the first quarter, while Intel, the only other significant competitor, dropped out of the race entirely, according to the research and management consulting firm.

Jon Peddie, a semiconductor expert who has been following Nvidia’s rise since its inception, said: “When you talk about competition, the competition is going to be for the cost-per-compute density.

“That gets translated into, how many processors can you stick in a chip and sell it for? And Nvidia has the enviable position of being able to offer more processors per square millimetre of silicon than any other company.”

SoftBank, the Japanese investor, has held talks with Intel about creating a rival AI chip, the Financial Times reported this week. However, it was reported that the talks fell apart because Intel was incapable of meeting SoftBank’s demand for scale and speed.

Harsh Kumar, semiconductor analyst at Piper Sandler, thinks it is unlikely that a serious rival to Nvidia will emerge in the GPU market. “There’s an incredible amount of software involved,” he said. “And then there’s the share cost. To design a chip like the Blackwell chip that is coming out by Nvidia … you will spend somewhere in that range, $500 million to $1 billion to come up with a chip that may or may not succeed in the market.”

He added: “There’s not a lot of companies that could take that sort of risk. And so you have the capital risk, you have the risk of software and the risk of extremely complex technology, and then you also have to manufacture this stuff, which is also incredibly hard.”

Nvidia offers Cuda data-processing libraries that can be applied to any sector from drug discovery to fraud detection and self-driving, providing a skeleton for what different companies are trying to accomplish. This is topped off with networking services to establish data centres required to run the GPUs.

“You go to Nvidia, it’s like going to Apple,” Kumar said. “You will get the air pods, you will get the phone, you will get the iPad, and you’ll get a watch. And when you walk out you’re decked out in technology, ready to rumble, ready to go. You don’t have to fool around with other people’s networking gear and see if it matches or works well, et cetera. So Nvidia, if you will, provides the total package.”

A group of rival chipmakers including Broadcom and Marvell are offering an alternative to the GPU, known as the application-specific integrated circuit (Asic). Whereas the GPU can be used for a multitude of tasks, from video games to generative AI, an Asic can be simplified so it only provides AI processors.

Google uses Broadcom’s specialised chips to train and run machine-learning models for its services, including Google Search and YouTube.

However, Google is still a big Nvidia customer, relying on its GPUs for Google cloud services, which require a more flexible chip.

Some of Nvidia’s biggest customers, including Microsoft, Apple, Amazon and Google, have started investing in their own chip designs, to reduce their reliance on the company. However, Nvidia does not appear to be at risk of losing their business because of its unrivalled scale, which means it can produce more chips at a lower cost.

Nvidia’s own annual report dedicates 17 pages to detailing all of the risks faced to the company’s results. They range from “failure to meet the evolving needs of our industry” and “dependency on third-party suppliers and their technology to manufacture, assemble, test of package our products”, to competition which could eat into its market share and the fact that “a significant amount of our revenue stems from a limited number of partners”.

Production of Nvidia’s chips is handled by manufacturers, such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.

The company is also drawing more attention from regulators who may be concerned about its market dominance.

A spokesman for Nvidia said: “Nvidia wins on merit, as reflected in our benchmark results and value to customers.

“We compete based on decades of investment and innovation, scrupulously adhering to all laws, making Nvidia openly available in every cloud and on-premises for every enterprise, and ensuring that customers can choose whatever solution is best for them. We’ll continue to support aspiring innovators in every industry and market and are happy to provide any information regulators need.”

Despite all of the possible headwinds facing the company, its results on August 28 are expected to demonstrate the huge demand for its products.

Dan Ives, an analyst at Wedbush Securities, said investors would be listening to Nvidia’s earnings call to get a steer from Jensen Huang, the company’s chief executive, about future demand for AI chips in 2025.

He said: “[At the] Nvidia earnings on August 28 you will be able to hear a pin drop on trading desks around the street/globe as investors hear from the Godfather of AI Jensen on the massive demand trajectory for AI chips into 2025 which we believe will be another drop the mic moment for tech.”

Post Comment